EMMETT TILL AND MAMIE

TILL-MOBLEY HOUSE

CURRENTLY UNDERGOING RESTORATION

FROM TRAGEDY TO TRIUMPH

WE’RE BUILDING A MUSEUM, THEATER AND HERITAGE HUB

Located at 6427 S St Lawrence Ave. in Chicago, IL

BIG is restoring the childhood home of Civil Rights martyr Emmett Till into a museum commemorating the Till Family legacy of courage and forgiveness. Located at the center of our West Woodlawn neighborhood, the museum will tell the story of Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley and their Great Migration family. The restored building will house a rich array of programming, ranging from education to performance while meeting the highest standards for net-zero energy performance and construction.

Designated as a historic landmark by the City of Chicago, the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley House celebrates the Great Migration story of courage, fortitude, creativity, labor and love that built so many great American cities. It is the crown jewel of the Sustainable Square Mile’s Black heritage tourism economy, rooted in the narrative of Black triumph and resilience.

Down the block from the house, BIG established the Mamie Till-Mobley Forgiveness Garden. A newly tree-lined path connects the two sites.

We secured historic landmark status for the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley Home from the City of Chicago.

PROJECT OVERVIEW

The Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley House was the residence of Emmitt Louis Till, a black teenager who was lynched in August 1955, while visiting relatives in Mississippi; and his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, whose advocacy conveyed the dangers of white supremacy to a worldwide audience. Blacks in Green bought the Till House in 2020 and in 2021 the Chicago City Council designated it a city landmark. Today, Blacks in Green is restoring the house as a museum and theater that will interpret and share the legacies of Emmett and Mamie; while investing in green and renewable energy systems that will serve the house and the neighborhood of West Woodlawn into the 21st century.

LOCATED IN WEST WOODLAWN, CHICAGO

In the mid-20th century, Woodlawn was middle class. Living conditions in West Woodlawn were of a higher quality than in other Black neighborhoods in Chicago, like Bronzeville, where conditions were cramped. The commercial thoroughfares of both Cottage Grove and 63rd Street provided means for entertainment and commerce and included restaurants, drug stores, ice cream parlors and filling stations, and theaters like the Tivoli Theatre at 6323 South Cottage Grove Avenue, and the Midway Theatre at 6250 South Cottage Grove. The East 63rd (Jackson Park) Branch of the Chicago elevated rapid transit system provided service outbound to Jackson Park, and inbound into the Loop. Streetcars ran on both Cottage Grove and 63rd Street. In Death of Innocence, Mamie states that Emmett would regularly take the 63rd Street streetcar from Woodlawn to Argo and that the trip would take less than a half hour. A train station at 63rd and Woodlawn provided the neighborhood with access to nationwide passenger rail via the Illinois Central Railroad, including the Spirit of New Orleans, which had regular service between Chicago and New Orleans, including stops in southern Illinois, Tennessee and Mississippi.

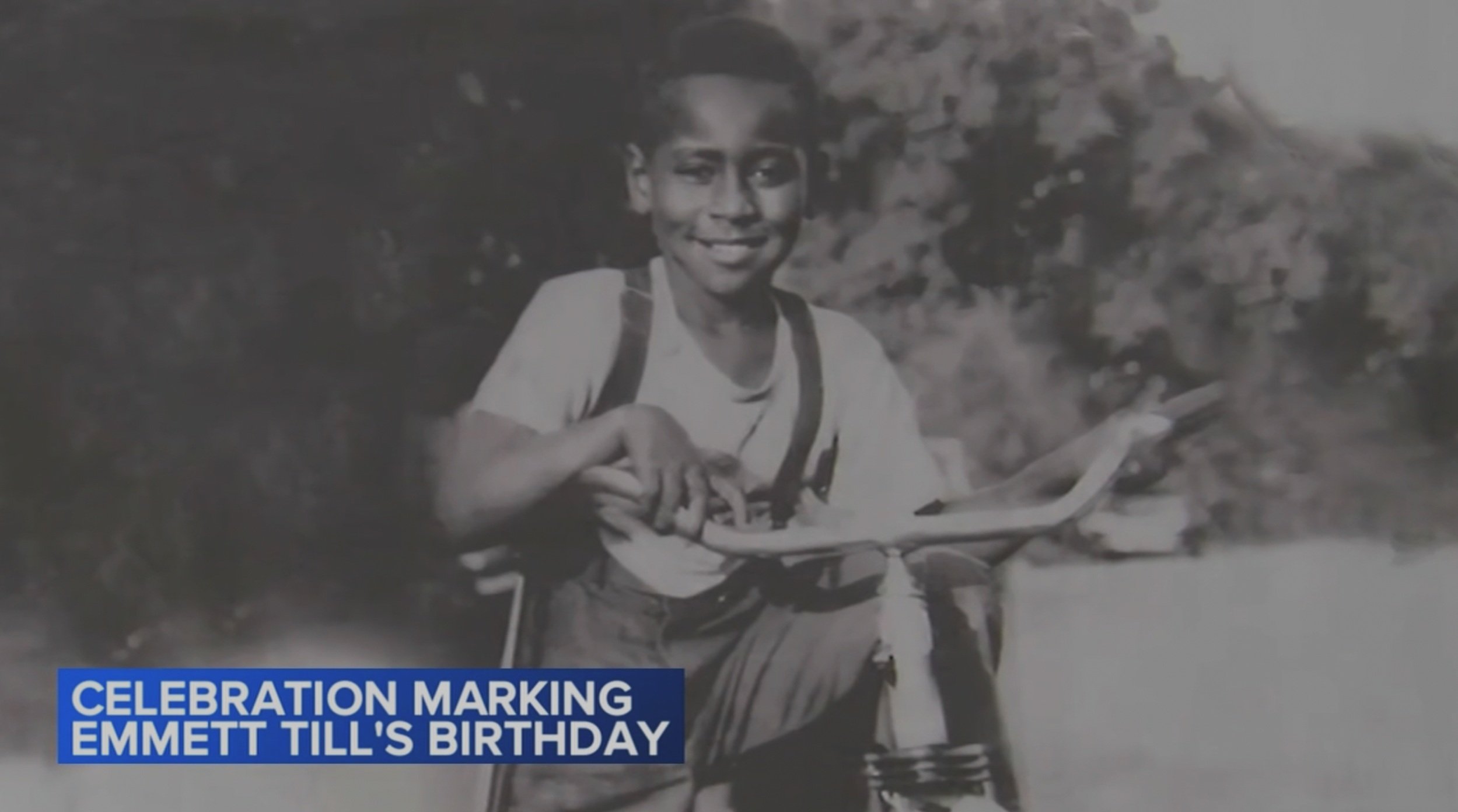

WHO WAS EMMETT TILL?

Emmett Till was a 14-year-old Black child visiting Mississippi relatives in the summer of 1955 when he was tortured and shot by white racists. His mother’s decision to open his casket for his funeral and allow photographers to document his murderers’ brutality galvanized the Civil Rights movement. Out of unspeakable tragedy grew a triumphant force that changed the nation.

THE GREAT MIGRATION

The Great Migration, a decades-long movement of Black Americans from the Southern to the Northern States, shifted Woodlawn’s racial demographics from majority white in the 1930s to majority black by the 1960s. The prevalence of passenger railroads to Chicago from southern cities to northern ones, particularly via the Illinois Central Railroad, made the trip geographically and financially possible, while migration chains helped those migrating find housing and employment, and build social capital. Migration Chains also facilitated ongoing visits by Black Americans who settled in the North back to their families in the South, particularly during the summer when children were out of school.

In Chicago, the Great Migration permanently changed the culture and racial demographics of the city forever. Chicago’s industries of steel and meatpacking were unattainable to Black Americans until World War I halted immigration from Europe. The need for industrial labor opened up the ability for Black Americans to work these jobs. Churches were established in the Baptist and Pentecostal traditions of the South, often in buildings that had been previously used for other purposes, or by white congregations. Black Americans faced limited housing options, leading to the segregation of the cities’ neighborhoods and cramped conditions where Black Americans could live. Artists in the blues and gospel traditions came to Chicago and found success, catapulting the sound to a worldwide audience.

We received a $150,000 grant from the Telling the Full History Preservation Fund for our work on the Emmett Till Home. The Fund is a joint project of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and the National Endowment for the Humanities.